Satellite photos give a striking look at the second most powerful meteor explosion of the 21st century.

On Dec. 18, 2018, an incoming space rock detonated 16 miles (26 kilometers) above the Bering Sea's icy waters, generating 173 kilotons of energy. That's about 10 times more than the amount unleashed by the atomic bomb the United States dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima during World War II, NASA officials said.

Only one impact event since 2000 was more powerful — the February 2013 airburst over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk, which produced a shockwave that injured more than 1,200 people. (Most of those folks were hurt by shards of flying glass from broken windows.)

Related: Photos: Russian Meteor Explosion of Feb. 15, 2013

Unlike the Chelyabinsk event, nobody on the ground saw or recorded the Bering Sea meteor, as far as we know. That's a consequence of the remote location; the Bering Sea lies between far eastern Russian and Alaska. But some sharp eyes in the sky did preserve the blast for posterity.

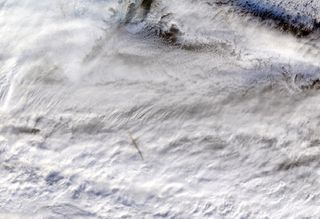

NASA's Earth-observing Terra satellite, for example, spotted the meteor with two different instruments — the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) and the Moderate Resolution Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MODIS). MISR team members combined some of their imagery into an animated GIF, which NASA released Friday (March 22).

Meanwhile, a true-color MODIS photo shows both the fireball and its dark smoke trail, which stands out prominently against thick, white clouds, NASA officials said. (In case you were wondering, "fireball" describes any meteor that shines at least as brightly as Venus in our sky.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Japan's Himawari satellite also observed the blast. You can see some of that spacecraft's photos in this Sky & Telescope story.

The object that caused the Bering Sea fireball was probably about 33 feet (10 meters) wide and weighed about 1,500 tons (1,360 metric tons), according to NASA meteor experts. The rock likely hit Earth's atmosphere going about 71,600 mph (115,200 km/h).

Scientists think the Chelyabinsk asteroid was about 65 feet (20 m) wide at the time of its dramatic encounter with Earth. That object's explosion unleashed a whopping 440 kilotons of energy.

But that output pales in comparison to a 1908 airburst over Siberia, which involved an asteroid thought to be about 130 feet (40 m) wide. This explosion, known as the Tunguska event, generated 185 times more energy than the Hiroshima bomb and flattened about 800 square miles (2,000 square kilometers) of forest. It's the most powerful impact event in recorded history.

And no, the gods don't have anything against Russia. Russia gets walloped by space rocks so much simply because it covers more area than any other nation.

- Huge Russian Meteor Blast is Biggest Since 1908 (Infographic)

- Potentially Dangerous Asteroids (Images)

- Meteors, Shooting Stars and Fireballs

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.